Written by: Richard Prieto, Cisneros Class of 2024

In the U.S., Black History Month reminds us of the contributions of millions of African Americans who have participated in the broader project of America. Every year, we acknowledge the achievements and impact that African Americans have had, and continue to have, in this country. Throughout much of Latin America, people of African descent also face the constant struggle for full equality.

In Nicaragua, the country where I was raised for most of my life, there are a little more than 500,000 Afro-Nicaraguans, comprising about 9% of the total population.

They represent the third largest ethnic group after whites and Mestizos (a mix between indigenous peoples and Europeans). Although they represent a significant portion of the population, the vast majority of Black Nicaraguans live in two particular regions of the country, the Región Autónoma del Caribe Sur (RACS), and the Región Autónoma Caribe Norte. The two regions combined, are two times bigger than Maryland and they are known for their large rivers, white beaches, and their infamous 9 month-long raining season. Such geographic characteristics have resulted in years of isolation and underpopulation in comparison to the major cities in the Central and Pacific regions where most of the colonization efforts by the Spanish were made.

Despite the fact that these regions represent more than half of the country in terms of area, they are also among the poorest regions, and their unemployment rates and rates of violence are also higher than in the rest of the country. The struggle of Afro-Nicaraguans persists even when they leave the precarious situation of their home regions for economic opportunities elsewhere, and they face discrimination when they move to the Pacific or the Central part of the country.

The struggle that Afro-Nicaraguans face is also one of visibility; because of the historical isolation of their home regions, a significant portion of the population in the rest of Nicaragua sees them as outsiders, with traditions and culture that seem “un-Nicaraguan.”

As non-black Nicaraguans, we need to start embracing the multicultural nature of our country. Nicaragua was not just made by the contributions of Spanish settlers and Indigenous communities, but also by the thousands of Africans who were brought to the country and made this country their own, as well.

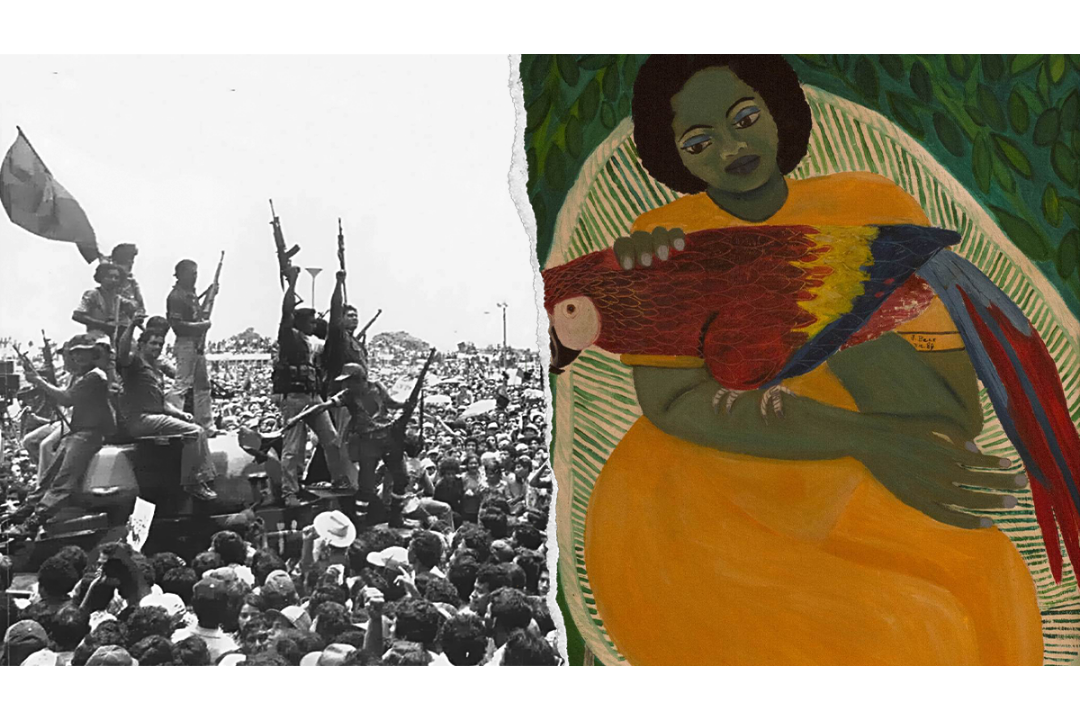

There is a rich culture and history of Afro-Nicaraguan activism that shows the desire for social change. Activists, intellectuals, and local leaders pressed the Nicaragua Government after the Revolution of 1979 to recognize the regional languages spoken in the Caribbean as co-official languages for the first time. This effort was led by an artist named June Gloria Beer. Beer was an Afro-Nicaraguan woman, who moved to the U.S. in the mid 1950s to become a painter. When her plans to become an artist in the U.S. didn’t turn out as planned, Beer moved back to Nicaragua, where she painted coastal scenes and travelled hours to sell them in the capital. A native to the Región Autónoma del Caribe Norte, she also revolutionized literature in Nicaragua, becoming the first female poet from the Caribbean Miskito Coast and the first Nicaraguan writer ever to use Creole and not exclusively Spanish. In her process of artistic and literary creation, Beer made significant contributions by spreading Caribbean culture to the rest of the country, which remained oblivious to the rich and fascinating culture of the Caribbean Regions.

After the establishment of the Revolutionary Government, she was named the head librarian of the city of Bluefields and, with the help of the Ministerio de Cultura, they eventually opened two public libraries in nearby towns. Beer wrote several books in Creole, English, and Spanish. Her magnum opus, El Funeral del Machismo, reflects on the double workload faced by women across the world and, of course, in Nicaragua.

Beer reflected on the fact that many women she knew worked all day to come home just to work again in household tasks with little or no help from their husbands.

Beer died in 1986 of a heart-attack in her home in Bluefields. 6 years before her death, a new Constitution was ratified; the first one in Nicaraguan history to recognize the autonomy of Indigenous peoples living in the Caribbean. Many activists have followed Beer’s example and continue to educate and spread their traditions and culture throughout the country. They have continued fighting to stop the discrimination against Afro-Nicaraguans and to give their communities the recognition they deserve in helping construct the Nicaraguan nation.

Richard Prieto is a first-year Cisneros Scholar in the GW Milken Institute of Public Health. Richard’s views are his own and not necessarily reflective of the Cisneros Institute.